Forgetting to Learn: Four Surprising Keys to Durable Learning

Whether cramming for a test, listening to a sermon or watching an instructional YouTube video, we all get that elusive feeling: "oh I got this!" We fall victim to the idea that learning is a passive activity. We even use language such as saying someone is a "sponge" when it comes to learning. But the truth is actually quite different.

In the human person, the sponge is strengthened by being squeezed, the spirit is emboldened by being challenged and the mind is broadened by what it produces not by what it receives.

When I worked as a business professor, I became very interested in the science of learning and how this could be applied in my teaching. What I learned shocked me. I had it all wrong. What I learned I began to apply in my teaching but also in nearly every aspect of my life.

We don't learn by what goes into the mind, but by what comes out of it.

1.Recall, rehearse, and link to what else you know

First, retrieval, rehearsal and elaboration is what we should be doing. The more we force our minds to recall information (to "go get it" from where it is in mind) the more we will own it and consolidate it into our longer-term memory.

Retrieval practice can take the form of just closing a book or notes and forcing yourself to recall them. Or it can be teaching it to someone else or testing or quizzing yourself.

Rehearsing is practicing the use of new knowledge through either visualization, simulation or embodied action.

Elaboration is the connecting new knowledge with existing knowledge.

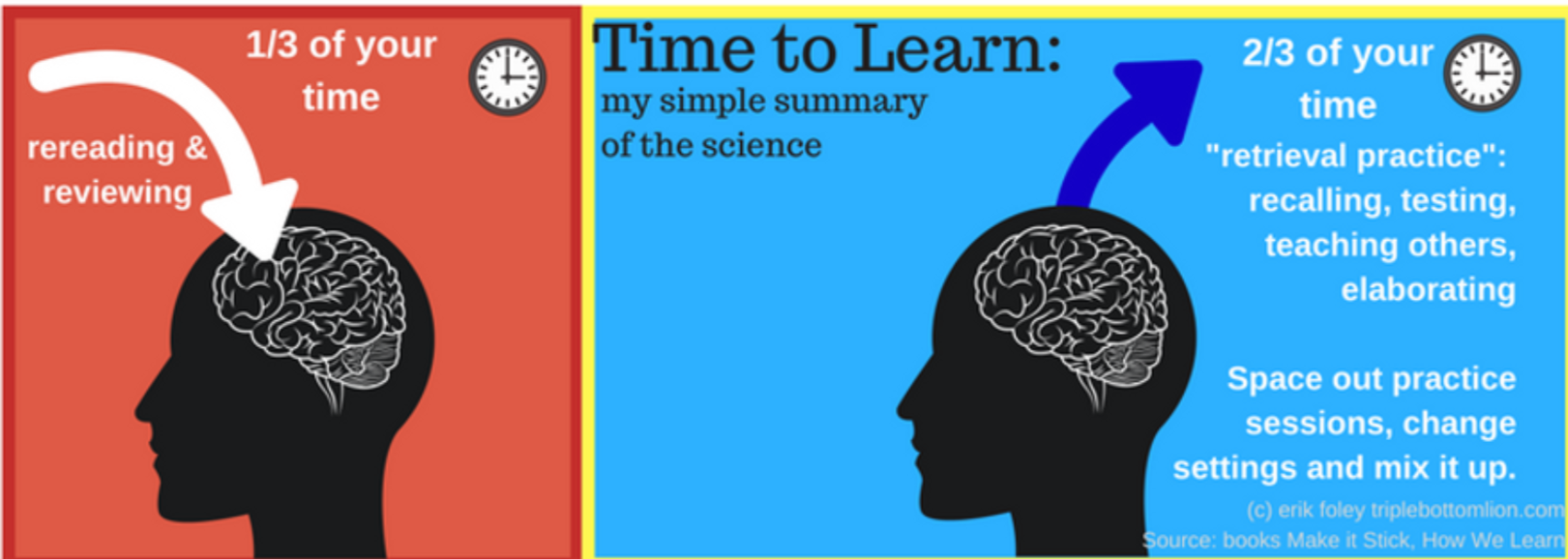

A good rule: 1/3 of your time should be spent reviewing new material and 2/3 should be spent in recalling the material. Most people have this completely reversed or spend no time recalling new information at all.

2.Forget to Learn: spaced practice, interwoven and varied

The researchers differentiate between massed, blocked practice and spaced, interleaved practice. The key is creating spaces of forgetting woven together with moments of powerful remembering. Let's unpack this further.

Massed, blocked practice can be illustrated by the young student learning how to write code and just keeps trying the same thing again and again and again. Many believe that this focused, vigilant approach is laudable and therefore effective for learning. While it might be a sign of resilience, it is not a sign of learning.

When we hear a great sermon or are inspired by a great speaker, that is another form of massed, blocked practice: all the content and activity is done in one focused block of time. This feels good and feels effective. But research suggests there is a much better way. What is more effective is spacing out learning events or practice sessions and what they call "interleaving".

Spacing refers to taking breaks and pauses between practice sessions. Ironically, spacing leads to some forgetting which turns out to be very important for learning. That’s why I have come to remember spacing as “forgetting to learn.” We have to forget something in order to remember it which is needed to truly learn and retain it.

Interleaving refers to the mixing up of skills or concepts or areas of knowledge. It is more effective for the student to practice coding for a time, then switch to, for example, learning about hardware, and then go back to coding. A golfer should not just practice one swing again and again. This gives the feeling of "fluency" but the superior way of practicing would be to practice your irons for 15 minutes, switch to woods, then to putting, then to chipping and repeat or mix it up.

Varied refers to a surprising finding from years of research: consistency is overrated

I know we have heard we should "get a quiet place to study and get into the habit of using it as your place to focus". But it turns out that varying the places where you study and learn is actually better. Go to the library a few times but then also try reviewing or testing yourself (or others) on the same information in a classroom or on a walk or in your apartment or at the gym.

3. Commit to the three keys to powerful life-long learning:

- Embrace a growth mindset: research suggests performance and learning are improved if you tell yourself (or your team, your students, your kids, etc.) the truth about the mind's "plastic" nature, that it is always growing and can be changed through practice. Your mind is changing and changeable!

- Practice like an expert: It is true what you coach (or music instructor) said: practice like you will play and you will play like you practice. Simulate how the new knowledge, skill or value will be used in the "real world" and practice that as much as possible. Vary the settings, opponents, conditions, types of songs, levels of difficulty. Practice doesn't make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect. Determine what your craft is and practice it as often as you can, in as many ways as you can and get feedback from the best people you can.

- Construct memory cues: mnemonic devices (rhyming, etc.) and memory palaces are powerful cognitive technologies used by "memory athletes"

4. Guard Against Illusions of Learning

We are experts at deluding ourselves. Motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, memory inflation, false consensus and a whole host of well-documented psychological mechanisms can keep us from understanding the truth of what we know and don't know, how we come across to others and what is really happening around us. How can we guard against these "illusions of learning"?

- Test yourself with regularity using some kind of objective measures

- Compare yourself to high-performing others in your field

- Gain feedback from others you trust and who will be painfully honest with you

- Use information from real-world settings and experiences. The simple habit of reflecting on your day can help you see your performance more objectively. Were you really as good as you thought you were? Or were you really as bad as you felt? Make notes on specific strengths and weaknesses in your performance.

Final Word - Wrestle the Bear

The harder the mind works, the more durable the learning. That is a simple but perhaps inconvenient finding of the research on learning. John McPhee's wise advice to a young writer with writer's block published in The New Yorker (April 29, 2013) get to the point: "Delete the whimpering and go wrestle the bear."

Wrestle with the new knowledge, new skill, and it will strengthen you in the process. Remember the simple rule at the beginning as a good starting point: 1/3 of your time to review material and 2/3 of your time to recall the information without notes, link it to what you already know and apply it.

Epilogue: Other powerful tidbits to super charge your learning (or teaching):

- The "testing effect" or the recall practice effect is very effective in moving thoughts and ideas from the short-term memory to the long-term memory part of the brain, and from information to action

- Frequent "low stakes" testing and low stakes quizzing with slight delays in feedback provide better learning and are often rated higher by students.

- The learning cycle: new information is encoded into “memory traces” and then consolidated, organized and connected to existing information. Then through retrieval and use it enters the long-term memory from the short-term memory.

- Consolidation is the process of new knowledge becoming organized and solid within the brain much like a rough draft becoming a final draft.

- Failure is key to learning. This is true not just because you learn from failure but because the search for answers and solutions itself prepares the mind for learning.

- Contextual interference is when learning is interrupted or haulted for the sake of reflection and consolidation. For example, this could be when a lecture is stopped to see what students are learning or misunderstanding. Or it could mean reviewing information in a different order than was presented in class or for a teacher in a different order than was presented in a book.

- Generation is important mental effort of thinking forward to a solution before the solution (or even the process for developing a solution) is provided. The speaker or teacher stops and asks the audience or class for a solution before all the information has been given

- Variation is changing the context and methods for teaching and learning.

Brown, Peter C. (2014). Make it stick : the science of successful learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts :The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press