How to Talk About Climate Change so People Will Listen

Our brains aren't ready for this.

Our top-shelf brains aren't good at long-term emergencies. Distant effects of our actions especially those that don't match our identity and world-view, are easily dismissed. Per Espen Stoknes, a psychologist with a PhD in economics, chairs the Center for Green Growth at the Norwegian Business School.

"Long-term surveys show that people were more concerned with climate change in wealthy democracies 25 years ago than they are today. So the more science, the more Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments we have, the more the evidence accumulates, the less concerned the public is. To the rational mind this is a complete mystery."

But to psychologists like Stoknes who know how our brain defends us against uncertainty, danger and despair, this is not such a mystery. Instead of pouring on more data and doom, let's get curious about how our mind defends itself and what approaches might be more helpful.

Five "psychological defenses":

- Distance - we have a hard time comprehending and valuing issues not in our personal space or direct proximity...so we don't

- Doom - we tend to be both fascinated and frozen with bad news (thus the dizzying amount of "click bait" and bad news stories); doomsday scenarios of rising sea levels might be scientifically reasonable projections but aren't correlated with motivating behavior

- Dissonance - when a tension arises between how we live (what we do) and what we know (our knowledge) we experience dissonance. If we downplay or tune-out what we know, we feel better about how we live and that’s often what people will do when dissonance comes.

- Denial - fear and guilt are very painful emotions that most people spend their time trying to avoid; denial is a handy device that allows us to push away these feelings and vilify those who would push them back in our face

- Identity - decades of research has pointed to our "confirmation bias" and "motivated reasoning" tendencies that make us see things, as Anais Nin once said, not as they are but as we are

So that's the defense we are up against. I played basketball in college and it was always important to know the kind of defense the other team was playing. There are different ways of attacking different defensive sets.

In the same way, to communicate effectively, it helps to know what defense you are up against. In our case we are facing down a lethal combination of distance, doom, dissonance, denial and identity. Any one of these alone could put the kibosh on your plans. We need a darn good offense.

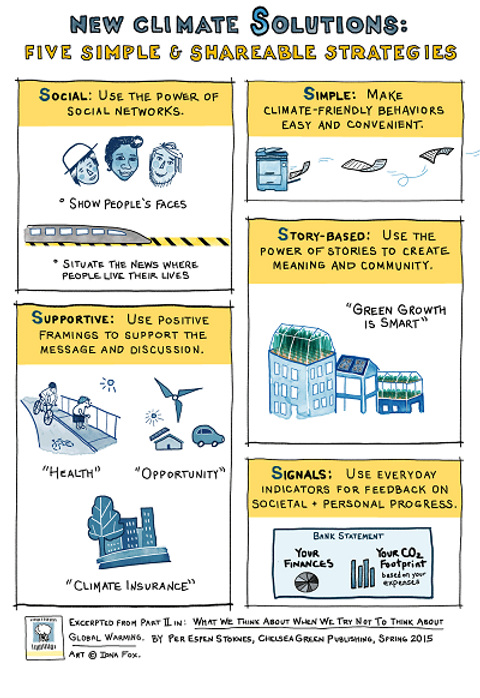

Five communication strategies:

- Make it social - people are strongly influenced by the behavior of their neighbors, peers and colleagues. Look for ways to provide what Robert Cialdini has called "social proof" that a particular behavior is preferred by the peer group.

- Supportive framing - rather than scaring the heck out of people with "end of times" scenarios, provide a hopeful message that presents climate change as an opportunity for innovation that is already being taken advantage of (note: research suggests that a mix of fear and hope is needed and that both negative and positive emotions can be motivating; it's the balance that is key and most climate change communication is too fear-driven)

- Simple - it is a frustrating paradox that something as complex as climate change must be simplified in our communications. Many spend their careers or if not some significant time understand its many complications, then we need to "dumb it down" when we talk to a general audience. Yes. But I prefer to say that we must "essentialize" the message without dumbing it down.

- Storytelling - you know the saying, "People decide with their emotions and then rationalize it with their mind." This is true and we can incorporate stories of people, communities, businesses doing the right thing. Choose stories that your audience will connect with.

- Signals - there is a problem with data: most climate data is global but actions must be personal (or at least organizational). The disconnect between the data and the actions can cause confusion or disempowerment. "How can I possibly do anything about it!?" Global data is important but it must be paired with data, what Stoknes calls "signals", that are calibrated to our actionable reality. For example, O Power's electricity bills that show your electricity consumption compared to your neighbors.

To learn more...