Five Resources Sustainability Brings to a Crisis (and Recovery)

In a crisis, sustainability needs to be at the table. The matrix of relationships, understanding of complexity, and penchant for courageous innovation among skilled practitioners make sustainability professionals key assets.

I will suggest five resources sustainability brings to the table during the crisis, during recovery, and in the renewed world to come.

- cross-functional agility

- stakeholder engagement

- seeing risks to the most vulnerable (as risks to everyone)

- think like a planet

- the future has arrived

We aren't EMT's or frontline doctors or nurses, but sustainability professionals are an essential part of the response team. First, let's bust two myths about sustainability in business We need to do some level-setting to ensure we are talking about the right kind of sustainability. Sustainability is often misunderstood in two ways:

- as being a luxury of wealthy countries and companies fortunate to have funding and staff to be concerned with long-term problems rather than survival

- as a necessary evil, a cost center required to keep regulators, quirky customers and advocacy investors at bay

If sustainability is (wrongly) seen as a luxury and/or a necessary evil, when a crisis comes around, we cannot expect much. The least we might do is ignore it and the most to liquidate it and fund more immediate concerns.

That would be a shame and a missed opportunity. We need the mindset and skillset of sustainability now more than ever. Business practice and research over the last 30 years has demonstrated that--when done right--sustainability is good business. Sustainability keeps a business engaging with relevant stakeholders, reducing costs and risks, and innovating new products and business models.

This is the kind of sustainability I am thinking about when I share these five resources sustainability brings to the table.

Cross-functional agility

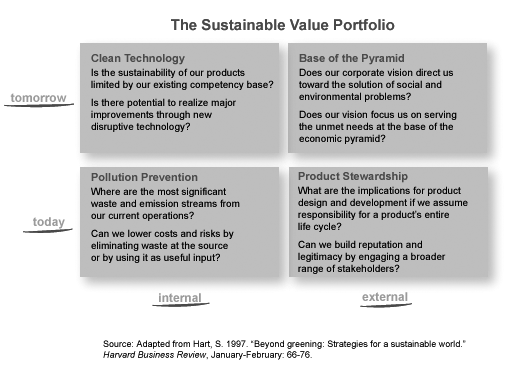

In his 1997 Harvard Business Review article Beyond Greening: Strategies for a Sustainable World author and professor Stuart Hart shared his vision for a Sustainability Portfolio (below): a 2 x 2 matrix of business strategies for near and long-term profitability and environmental/social benefit.

The framework is a guide for strategy but it also points to the need for something new: effective work across silos in order to achieve impact. None of the four strategies can be accomplished by a single department. Hart, like many scholars and practitioners since, has called for the integration of sustainability across the enterprise.

In short, don't just create a department or office. Create a new strategy, a new culture, of sustainability.

Here we are, 23 years later, and sustainability is profoundly cross-functional. The best sustainability professionals and teams are multilingual, able to listen and speak effectively with field sales staff, R&D engineers, investors, and human resources in the same day.

In times of crisis, the network of relationships sustainability professionals have constructed can be repurposed for agile responses to urgent needs. This network is both internal (cross-departmental and cross-functional) and external (cross-sectoral and even across-the-street). The best sustainability teams are embedded in webs of relationships ranging from global to local, that is, in the community with local businesses, non-profits and civil society groups.

The natural networks sustainability professionals have created can be a valuable resource during times of crisis when lines of communication and collaboration are needed--and we don't have time to create them. They must be there already and sustainability should have already built many of them.

Stakeholder Engagement

The seminal 2007 Harvard Business Review article Strategy & Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility by Michael Porter and Mark Kramer stated: "When looked at strategically, corporate social responsibility can become a source of tremendous social progress, as the business applies its considerable resources, expertise, and insights to activities that benefit society."

During a pandemic, when a distillery makes hand sanitizer or an OEM starts to make ventilators or a 3-D printing company makes masks, these are manifestations of a core idea of sustainability: business is in constant, active relationship with society and the environment.

In sustainable business, the relationship between an enterprise, society and the environment is most accurately portrayed by nested concentric circles showing business embedded within--and reliant upon--the larger systems of society and ecology.

"Business cannot succeed in societies that fail" is an often repeated axiom in sustainability. It is also true however that societies cannot succeed, as we are now seeing, with businesses that fail. And neither can succeed when the environment fails.

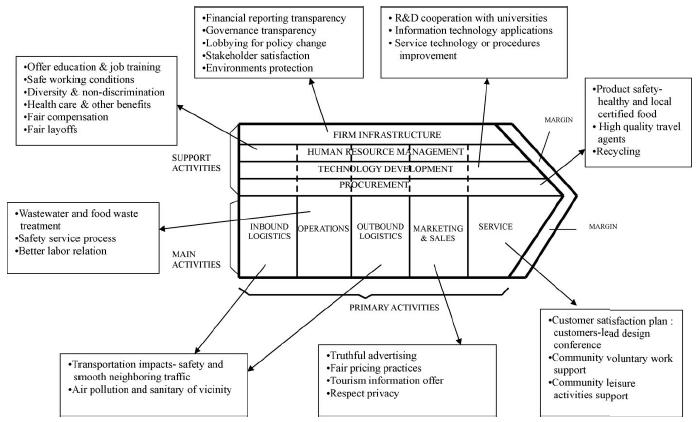

What we know about stakeholder engagement that can help in this moment and the recovery is this: your greatest contribution is often specific not generic. In other words, what can your business contribute based on your unique assets, abilities and networks?

Here's the bottom line: the best sustainability people are excellent at identifying external stakeholder needs, translating them into internal opportunities, and facilitating cross-functional processes to create value.

We need sophisticated stakeholder engagement skills in a crisis and skilled sustainability teams should have them in abundance.

Seeing Risks to the Most Vulnerable

Many have pointed out that the coronavirus has revealed health and economic disparities within and between nations. This was not a surprise for those working in sustainability. As a core responsibility, sustainability professionals constantly scan and consider social and environmental impacts, risks and opportunities--laddering up from the local to the global and back down--as a daily part of their work. They regularly scan news and social media for these "externalities" which sooner or later present a combination of threats and opportunities to businesses, their customers and value chains.

Many are still surprised that issues of equity are a part of sustainability. (sigh...) Let's take a quick trip back to the 80s to once again make the point that sustainability is NOT just about the environment.

The modern concept of "sustainability" is often thought to have been born out of the 1987 UN report Our Common Future: The Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Much like today's Sustainable Development Goals, the report talks as much about the need for addressing inequality, poverty, and gender discrimination as it does for environmental conservation. And here's the point: you cannot have one without the other. The foreword states: "These links between poverty, inequality, and environmental degradation formed a major theme in our analysis and recommendations. What is needed now is a new era of economic growth - growth that is forceful and at the same time socially and environmentally sustainable."

Why does this matter? Sustainability allows us to identify and assess risks and take proactive steps to avoid or mitigate them.

For example, a sustainability perspective would have predicted that the stacked issues of economic disparity, health disparity, environmental injustice and racism would make the most vulnerable populations the most susceptible to the coronavirus.

Many seemed surprised by COVID-19's disproportionate impact on people of color and low-income communities. Surprise is expensive. Surprise endangers lives. Sustainability can help avoid surprises and ensure policies and interventions are efficient since they will actually address where the problem is most acutely felt: among the most vulnerable.

Why play whack-a-mole with the problem when you can rely on sustainability to show you where to focus?

Think Like a Planet

A common refrain is that the coronavirus made us realize how interconnected we are. This is hardly a novel idea to those working and research sustainability. Indeed, a well-known axiom from the environmental conservation family line of sustainability is Aldo Leopold's "think like a mountain". From Leopold's 1966 classic A Sand County Almanac, this parochial-sounding, almost poetic notion has taken on a tenacious urgency with the coronavirus. Leopold was inviting us to appreciate the vast interconnected web of life in all our human decisions. Today, "thinking like a mountain" is hardly just a romantic notion but instead could be regarded as advanced risk assessment and mitigation.

Today, we might say the goal should be to think like a planet. And to act like one. What if we "thought like the planet" in all our decisions?

In business schools, we teach young people to think like an accountant or a supply chain professional or investor. And we should continue to do so! But it is odd that we don't also teach them how to think like a planet since they will work and spend their life on one.

Practically speaking, to think like a planet might mean that every business should consider forming some kind of scientific advisory board. Today, scientists are perhaps the best proxy we have for inviting tropical forests, oceans, the climate, and the world's poor and underserved into the board room. We need people who think like supply chain managers since we need those running smoothly. But we need them working with ecologists, hydrologists, biologists, climate scientists, epidemiologists, and more.

During COVID-19 pandemic, I interviewed Elizabeth McGraw, Director of Penn State University's Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics about the zoonotic diseases like the coronavirus. McGraw herself is an entomologist. One thing she made clear is that our degradation and fragmentation of ecosystems is giving rise to more spillover of pathogens from animals to humans. Much of this ecological impact happens in the deep supply chains of companies. The issue is that not many supply chain managers are talking to entomologists--or vice versa. But that can easily be changed as we begin to think like a planet.

Thinking like a planet might help us avoid problems we would otherwise create. Indeed, the best way to solve a problem is not to create it in the first place. Dan Heath puts this principle best in his new book Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen: “If you think about the way we conceive of heroes, our schema of heroes, we're thinking about people who rush in when there's an emergency, the firefighters who put out the flames in a burning building, or the lifeguard who jumps in the pool to save the drowning kid, or the policeman who come to fight off a burglar, or whatever, but what I want to point out is that an even better hero is someone not that saves the day but keeps the day from needing to be saved… the need for heroism is usually a sign of systems failure. [my emphasis]”.

Sustainable business innovators have been "thinking globally and acting locally" for decades. It is unfortunate that instead of taking advantage of this unique capability, most companies have stripped sustainability down to some vanity projects, LEED-buildings, and glossy reports. This is like using your smart phone as a coaster. It works, but it can do a whole lot more.

The Future Has Arrived

A favorite pun of mine goes like this: "I was wondering why the baseball was getting bigger, then it hit me." (cue laugh track...) This is actually a good way of making sense of how the field of sustainability has matured.

What we now call "sustainability" was originally inspired in the 1970s and 80s with predictions about the future: the accumulating effects of pollution, population increase, resource depletion, climate change, inequality, etc. came from books like Silent Spring, Steady State Economics, the Population Bomb and Limits to Growth. These predictions, like the baseball, keep getting bigger and bigger (that is to say, closer and closer) until they hit us.

What was predicted is what is happening. The predictions are not perfect and some will excoriate the authors for lacking precision. However, the basic plot line they envisioned is playing out: "If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years." (Limits to Growth)

This looks today like more hurricanes, more droughts, more wildfires, and more frequent and wider-spread infectious diseases from Ebola to MERS to SARS to Lyme to COVID-19.

I am not a doomsday-er. I am a very optimistic person and I believe in the power of human intelligence, creativity, and moral courage. But I also believe that we have to be brave enough and honest enough to face the facts as they are--not as we wish them to be.

Sustainability is a field that started with predictions and has entered predicaments; a handful of "hand waving" scientists has now has become a "hand wringing" public; what started as the warnings issued by a few and has become the worry and anxiety of the masses.

Of course, there has been unprecedented progress in medicine, technology and human ingenuity. The halving of extreme poverty around the world in the last 10-15 years is an incredible accomplishment. However, many of the predictions being realized are less rosy, as our sheer numbers plus the production and consumption of resources are pushing us against the constraints of our planetary system. Climate-related disasters, a rise in infectious diseases, a global refugee crisis, just to name a few, are inevitable results of a system that hasn't yet learned how to live equitably and within limits.

The future is far away, until it hits you. Sustainability can help us with our near-sightedness and to catch the ball before it careens off our heads.